Racing at the edge of the world

Nelson Trees is the founder of a cycling race that runs 1670km through the wild, remote mountains of Kyrgyzstan, which Red Bull calls “the toughest race in the world”. Formerly part of the Soviet Union, Kyrgyzstan is a landlocked country bordering Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and China.

“I left knowing very little about Kyrgyzstan” says 30-year-old Nelson in the documentary Wild Horses. In 2013, he cycled from Shanghai to Paris passing through Central Asia, on a carbon fibre tandem that he built with his dad.

“As soon as I arrived, I realised that it [Kyrgyzstan] was exactly what I had been looking for – expansive spaces, extensive silences, and breathtaking mountains as far as the eye can see. Here, in the heart of central Asia, I felt at the edge of the world.”

In 2016 and 2017, Nelson went on to complete the Transcontinental Race across Europe, finishing within the top ten both times, and in 2018 the inaugural Silk Road Mountain Race (SRMR) was born. The Silk Road, from which the race takes its name, is an historic trade route that passes through the country connecting East to West.

“I was inspired to launch the race after participating in the Transcontinental. Mike’s [the late Mike Hall] idea of a race that crosses a continent entirely under your own steam, with no support and following the route of your choosing, was revolutionary for me.”

Unlike the Transcontinental, the SRMR follows a fixed route, meticulously designed by Nelson, but like the Transcontinental is unsupported, with competitors fending for themselves until they reach one of just three staffed checkpoints. Competitors have two weeks in which to complete the race.

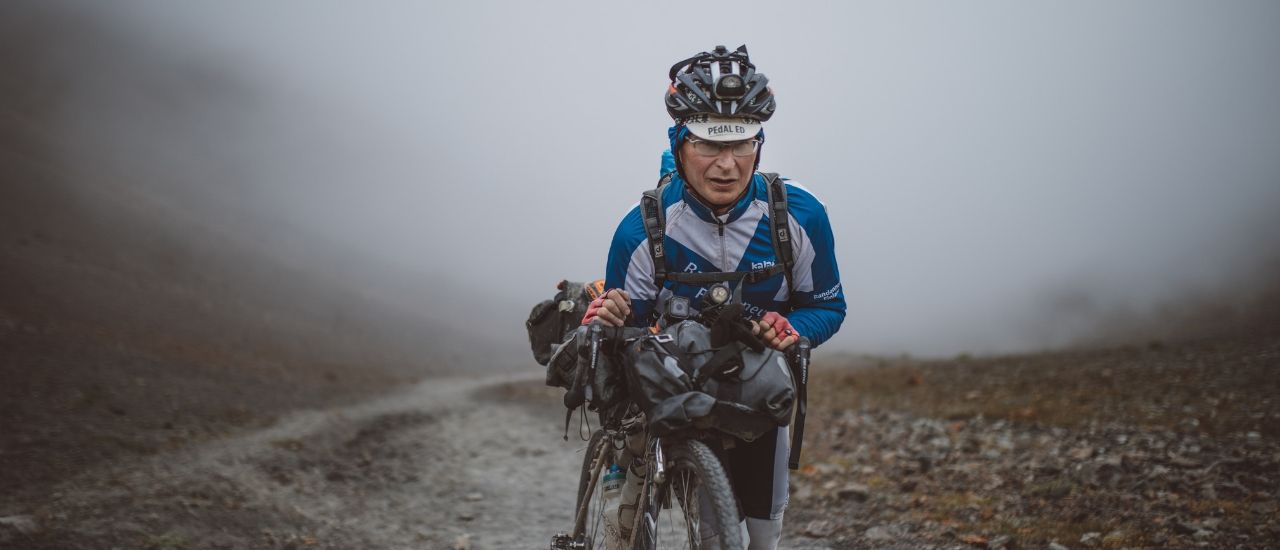

Departing from Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, competitors follow remote gravel tracks and forgotten Soviet roads through mountainous, mostly deserted land. “It is an adventure in which the landscape dictates the rules” says Nelson. Last year, only a third of competitors who entered the race completed it.

The toughest section of this year’s race, says Nelson, will be the 20km-long, 3800m-tall Shamsi pass – a sheer gravel mountainside carpeted in scree, which competitors must bike or hike their way across. “It’s a serious slog with little opportunity to back track if conditions are bad,” warns Nelson. “Everything will depend on the weather. One rider can have a completely different experience of the same section if it’s sunny or if they’re in the middle of a snowstorm.”

We ask Nelson what his best piece of advice is for competitors in the throws of sections like Shamsi pass. “All things end, whatever it is that is making a section difficult, it will pass,” he says. “It’s hard to remember this at the time but it can be the difference between continuing and scratching from the race.”

It’s at these challenging sections where Nelson notes that being an athlete is not what will win you the SRMR. The difficulties that competitors face take it beyond most other long-distance cycling events, and a combination of biking, hiking, and outdoor skills are required to do well. “It’s a test of your ability to evolve in the great outdoors. It may be a cycling race but it sometimes feels like a multisport adventure race because of all the different things you need to be good at,” says Nelson.

I think it’s fair to say that all endurance cyclists have a bit of a wandering soul

Mental resolve and a willingness to submit to the unpredictability of the weather seem at the core of the race, and it takes a certain kind of person to relinquish control and adapt to such harsh, threatening environments. “I think it’s fair to say that all endurance cyclists have a bit of a wandering soul,'' says Nelson.

Interest in the race has surged since its first year. Last year Nelson received 98 entries, and so far 150 competitors have entered the race departing 17 August 2019. “The destination itself is a big draw, Kyrgyzstan is still a relatively unknown, exotic and enticing location for a race like this,” says Nelson. “There are few places that have such an abundance of wilderness to explore.”

But even in its first year, the race drew well known names in the bikepacking and adventure racing community, like the 45-year-old American Jay Petervary, who won the race in eight days, eight hours, and 15 minutes, and the Belgian Kim Raeymaekers, who was first to reach checkpoint one, but scratched before checkpoint two.

Aside from the popularity of the race itself, Nelson notes that the popularity of ultra-endurance events has increased exponentially in recent years, and that races like his provide an antidote to our modern, cosseted lives. “Many of us live very safe, protected and predictable lives, and people feel the need to escape this and head back to their roots” he says. “Doing something where you can test yourself and where your actions have direct consequences is exciting.”

Despite this, it’s clear that Nelson, who now lives in Kyrgyzstan, is keen to maintain the race’s community bent. “I wanted to recreate something with the same ethos and sense of community as Mike’s Transcontinental Race elsewhere,” he says. “I wanted to share a new location with the cycling community.”

And, although the SRMR is a seriously challenging race attracting big names and competent riders, it seems as though it is as much about biking as it is about experiencing a side to Kyrgyzstan that few people ever will. “There are few, if any, bigger groups of tourists heading out into the Kyrgyz backcountry,” says Nelson. The race, he says, has a direct impact on the local communities it passes through. “The riders are all independent travelers with a high level of understanding of how to behave, leaving no trace and being respectful of local culture.”

There’s no glory affixed to the winners of the winners of SRMR, winners don’t receive gifts or prizes, just a small posy of flowers, and there’s no large crowd waiting to cheer competitors through the finish line. Neither is the race a battle of resources, with the entry price deliberately set at a reasonable £300.

“In the end, the race is about facing the elements by yourself, getting through it with your own resources and abilities, and that’s what makes it so rewarding,” says Nelson. “Riders every year learn a lot about themselves, push beyond what they thought were their limits and come out that much stronger because of it.” What better prize for a race like the Silk Road Mountain Race could there be?

Last year, Firepot-fuelled Pete McNeil was one of the few riders to complete the SRMR. We spoke to him about what it was like to be part of the inaugural race.

In 2019, 20 riders packed Firepot for the more remote sections of the route.